When one person's failure is another's innovation: The About Me Boards Story

I wrote recently about one of our team's favorite axioms: solve within arm's reach. This is our reminder it's not only easier, but considerably more enjoyable to quickly chip away at a challenge rather than trying to boil the ocean. The trick, particularly for me as someone inclined to things that are big and bold and disruptive, is learning to foresee complexity in a project. Often, the thing we think seems simple enough can get overwhelmed by red tape, complexity, and the cacophony of minor obstacle. Those moments are exactly the best time for someone with fresh eyes to see the simplier path forward.

Three years ago, we were working on improving the transition from a hospital stay to going back home. One particular interview with a patient became the spark ignighting one of my favorite design projects. Today, as I reflect on the project, I think of it as a story of gratitude for our nurse colleague who figured out how to solve within arms reach.

One of my innovation team colleagues and I were visiting with a patient in their room. We were interviewing him for this transitions of care project. Initially, the patient, while not standoffish, was also not particularly talkative. He was, however, keeping a journal with his own meticulous notes. During our visit, a physician entered the room without knocking. The physician did not introduce himself to the patient or my colleague and I. Instead, he briskly pulled back the patient's sheets, looked at the surgical site, and announced: "Looks good. You'll probably go home tomorrow". With that, the doctor turned on his heels and left.

We then asked the patient: "Tell us what that experience, that encounter just now, was like for you?" The patient sat up in bed. He turned his notes to us and said: "I've been keeping track of everyone who comes in my room. I've also been noting who washes their hands. Your nurses are fantastic, I think they're at 100% with handwashing. That doctor didn't wash his hands." The patient became more animated. "Also," he said "I'm a physician too. He didn't have to speak to me so abruptly. In fact, I would like to have discussed some details."

We were both blown away! My colleague asked: "what else do you wish that physician had known about you?"

"Well," he started, "I run a national network of long-term care facilities. We tell all of our patients to bring in pictures of themselves so everybody can see who they are when they are not in the hospital. That way, nobody ever gets treated as the knee in room 428."

There it was was. That was the spark. It immediately felt consistent with themes we heard from other conversations: most people, when lying in a hospital bed, don't think of themselves as the patient first (or even at all). We asked the brainstorming question:how might we help anyone entering a patient's room see that person's non-patient identity? The brainstorming didn't take long. We immediately turned to the newest member of our team, our engineer in residence.

Together we conceived of a display that would sit over the head of the patient's bed. The contents of the display —photos, a real-time pain scale, and a list of hobbies or interests —would be in control of the patient or their family through some kind of mobile device interface. Technically the concept is fairly easy to implement. We even had a small grant to cover a pilot in 5 to 10 patient room. But, the deeper we got into the project, the more unforeseen tiny obstacles started to add up and feel insurmountable. While we were ringing her hands over little things like getting access to a Wi-Fi network, or a determination if Bluetooth met our HIPAA security requirements, Matt, a nurse on our team, seized the opportunity.

Matt began iterating on the idea quickly. He used PowerPoint to create a poster template. Whenever there was a new admission, he would spend 30 minutes getting to know the patient, their interests, their background, and their hopes and goals. He would then quickly fill out his PowerPoint template and print on our large-format poster printer. He started hanging the posters above or near patient's beds.

Matt soon realized even his expedited process was a bit too intense for him to maintain. He made a smaller version of the template and trained some of the hospital's volunteers on filling it out. Together, Matt and the volunteers begin to realize the value was in the conversation they were having and the printout with simply an artifact.

None of us predicted just how powerful that artifact and conversation would be. Patients began taking their printout — which at this point we began calling About Me posters — home with them. One family wrote a note to Matt telling him it was the first time they had ever kept something from a hospital. Another one of Matt's older patients, sadly, passed away. Shortly after the funeral, his adult children contacted Matt tell him they had taken his About Me sign to his funeral and set it near the casket. They said: "this was one of the last conversations dad had with anyone."

Last year, shortly before we opened our new patient care tower, Matt came forward with an idea. He had identified some unused section of wall space in every patient room. He suggested we install a simple whiteboard pre-printed with three questions:

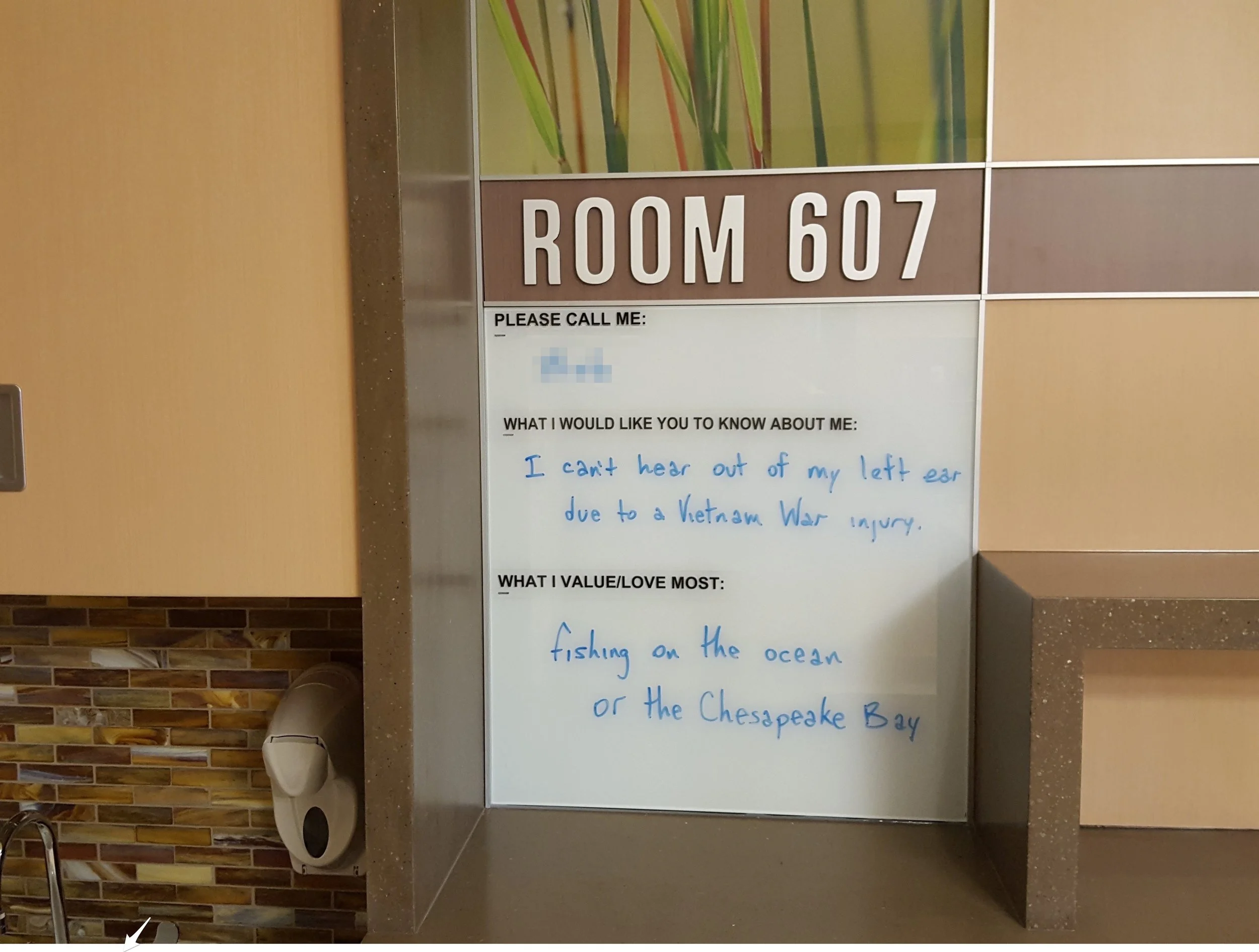

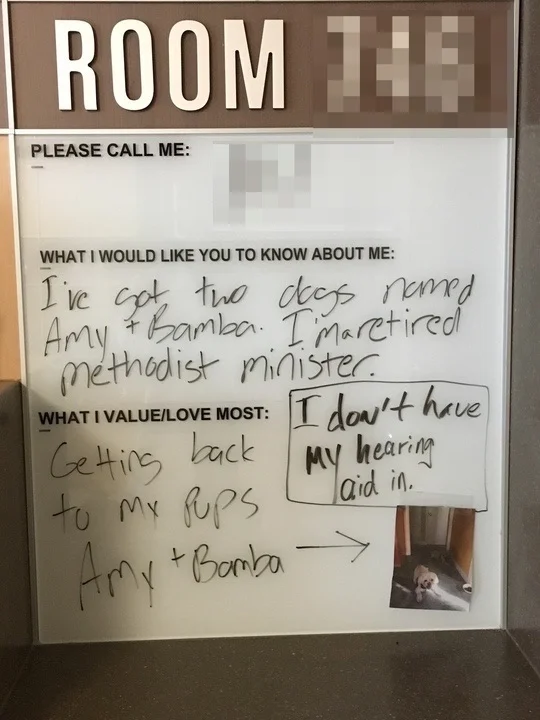

- Please Call Me:

- What I would like you to know about me:

- What I value/love most:

Those simple prompts were distilled from Matt's iterations with the poster and smaller printout versions of the signs. He called it the About Me Board and successfully lobbied to have one installed and every patient room in the hospital. The goal was to give everyone a simple tool to enable the same powerful conversations he had been having with his patients. Anyone who enters a room could instantly and confidently find something to talk about with the patients; something human and personal to them, something outside of the clinical relm, something that builds a deeper connection.

There have been some amazing stories from the About Me boards. One patient told their nurse all about their two dogs and how much they meant to her. The nurse asked the patient to email her some pictures of the doggies. She printed them out at her nursing station and taped them to the About Me board in the patient's room. In another story, a physician entered a patient room for daily rounds. She glanced over at the board and saw the patient wanted to be called "birdman". She looked at the patient and said, "I certainly will not call you bird man!"

To which the patient replied laughingly: "I just wanted to make sure you were going to read it."

About Me boards have woven themselves into the fabric of our organization. For clinicians, they provide a humanizing reminder that the person in the bed is not their diagnosis. For managers, in a second's glance, they bolster confidence by providing an opportunity for a non-clinical conversation. But most importantly, for patients, the About Me boards provide an opportunity to feel valued, heard, and treated like a full person.