Do scary things with people who make you feel safe

This post is part of a series: 5 things skiing taught me about leading change. You can find the other posts in this series here.

pausing for selfies after skiing triple black chutes

Our mountain has some of the most insane in-bounds terrain in North America. I have wondered often which lawyers even signed off on allowing some of our runs to be actual ski slopes. A lot of our advanced, high-alpine terrain pushes my limits. Some of the areas are what we call high consequence. I remember going out with a group of other instructors to tackle some of the rarely opened extreme terrain. On the way up, one said, “y’all know all the stuff that can go wrong like falling, or catching an edge, or popping out of your skis? Yeah, just don’t do any of those things up here.” It was meant as a bit of levity but the underlying seriousness wasn’t lost on me.

These high alpine settings require skiing with things like avalanche beacons (radios that help someone locate you if you’re buried) and shovels (see: avalanche beacons). At the top of each pitch, we paused and made a game plan. We decided who’d go first, and who’d go last. We talked about which turns to make sure we made and where we needed to be extra alert. We pointed out cliffs to avoid, lines to take, and places to meet.

Skiing that kind of terrain is exhilarating and terrifying. It tests everything in your skiing, gear, and concentration. And it’s not the kind of thing you do alone. Having a crew of people who were all invested in each other's safety makes it not only more survivable, it makes it more enjoyable.

Countless guests told me some version of the same thing: “I don’t know what it is, I just feel better skiing when I follow you.” I started calling it Red Coat Syndrome after the color of our uniforms and as an inverse reference to white coat syndrome —the term we use to describe someone having atypically high blood pressure simply by being in the doctor’s office. Whenever I had a guest or group of guests who were ready for more advanced runs, I always asked how they felt about trying something a little more challenging. For a beginner skier, skiing your first intermediate run has the same mix of exhilaration and fear I experience staring down a triple black chute. And for many guests, knowing I was going to be in front of them, helping them pick the best line, and ensuring their success was a huge part of being willing to say yes.

I was recently asked what I thought was the most important part of a team’s culture. I’m biased because my answer is what I most want in any setting: psychological safety. Psychological safety is the ability to speak your mind freely without fear of judgement or consequence. On the mountain, it was being comfortable saying “y’all, I’m a little freaked out by this chute” and knowing my crew was going to talk it out rather than shame my fear. (Don’t get me wrong, ski instructors aren’t saints to each other, the jokes are fierce, but encouragement is always genuine and caring.)

Design is fundamentally about empathy, humanity, and creativity. The teams I’ve led work best when someone can bring their full self to the work. Bringing your full self to work is a phrase that is au courant in job descriptions, but in my experience, when you are working on complex, human-based, healthcare challenges it is critical that someone on the team can actually talk about their own lived experience as an underrepresented person, a disabled person, a caregiver, a parent, etc freely. When we brainstorm, we say one of the rules is suspend judgment. A colleague used to encourage brainstormers to come up with illegal, immoral, and impractical ideas as a way of unlocking creativity. Psychological safety is key in being able to toss out something wild that just might solve the challenge.

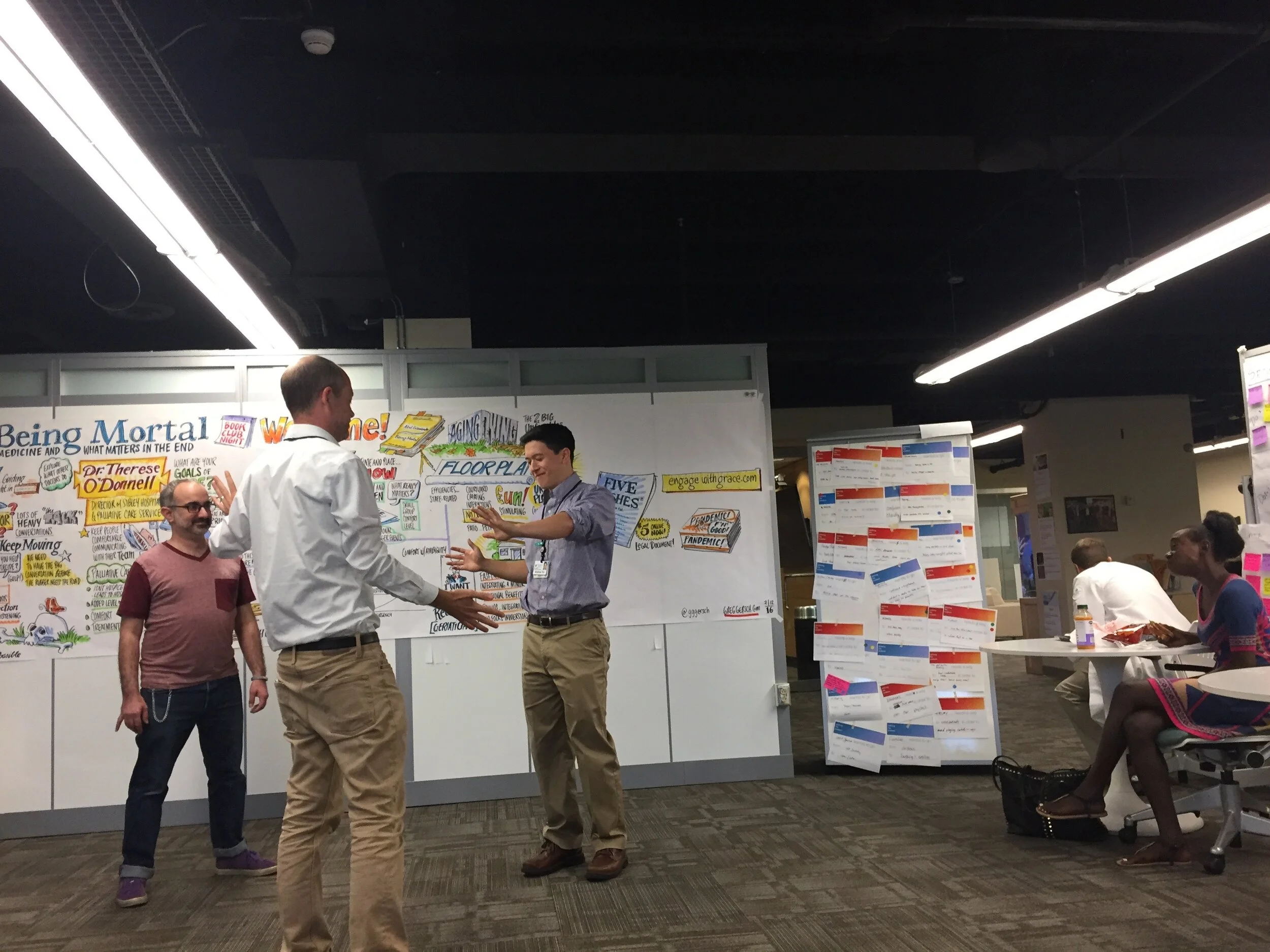

our innovation team in the middle of an improv class. doing improv comedy is all about trusting each other, being willing to take risks together, and psychological safety.

Psychological safety is also what allows someone to speak truth to power. I remember a challenge one time with an employee. I was convinced with enough coaching we could turn his challenging behaviors around. After enduring his disruptions way too long, two other employees literally pulled me aside and said: “your inaction here is making us question your leadership, it’s not a good look and we’re concerned you aren’t seeing the effect this has on the team.” That’s all it took, I made the decision to help our disruptor move on asap. I often look back on that moment with tremendous appreciation. My colleagues felt safe enough to come to me with honesty and candor, knowing it wasn’t going to blow back on them.

a prototype “break cart” - a break on wheels for busy nurses

The strength of teams that actively cultivate psychological safety is in being able to do scary stuff. Challenging the status quo, asking leaders, organizations, and teams to change isn’t easy. Once we were asked to look at nursing workflows. After embedding ourselves with nurses for a month (including visiting them at home and following their commute), we realized that we weren’t working on a workflow issue.

We were working on a culture issue and one of the biggest challenges was coming from nursing leadership. Packaging that finding and sharing it with the rest of our leadership team —along with some prototype solutions —was a terrifying experience. In that room, I didn’t have a team who made it safe to do scary things. The end result was, raised voices, finger pointing, and nothing that was aimed at helping our nurses.

The missed opportunity was not taking some of that leadership group on the journey with us. If I had involved them in the same deep research my team had done, we’d have been able to support each other when we had to tackle the scary part of sharing the results with the rest of our leadership cohort.